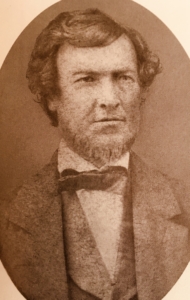

Parson Clapp of Appledore - Jerome's Father

In 2007, Peter Christie, a noted Devon historian, unearthed the full story behind the Jerome family’s mysterious and precipitate departure from Appledore to Walsall, four years before JKJ’s birth. It is an extraordinary piece of research and the Society is immensely grateful to Mr Christie for allowing his essay to be reproduced here.

THE REVEREND JEROME CLAPP IN APPLEDORE 1840-1855

One of the most popular English fictional works is Three Men in a Boat. First published in 1889 it went through many editions and is still in print today. Its author was Jerome K. Jerome whose father was Jerome Clapp Jerome or, as he was more commonly known, Jerome Clapp.

It is not generally realised that Jerome senior had close links with Devon having spent some 15 years in Appledore. This article will examine his life here in the county which is both fairly typical for a nineteenth century nonconformist minister – and yet rather more colourful than most. It will also explore certain aspects of Appledore’s past – a settlement which still awaits a definitive history. The whole is based on evidence from newspapers, books, court cases and oral tradition which is presented chronologically.

Jerome senior was born in London in 1807 and though there was a claim that he attended the Merchant Taylor School this is almost certainly incorrect. [1] Another possibly incorrect claim is that he began training as an architect before leaving ‘still in his teens’ to enter the non-conformist ministry. He attended the Rothwell Nonconformist Academy in Northamptonshire and, although possibly never becoming fully ordained, became minister at the Independent Chapel in Marlborough, Wiltshire around the age of 21. From here he moved to Cirencester and then to Dursley. In August 1840 the Independent congregation in Appledore invited him to become their minister. [2] This group was established around 1662 and latterly worshipped in a chapel that had been enlarged in 1816 to hold some 570 people.

In the Census of June 1841 Clapp appears listed first in a household occupying a house on Marine Parade, Appledore. [3] This would appear to be the prominent corner house that still stands today at the junction of the Quay and Marine Parade in the village. Four other people are listed; Ann Morgan aged 70 and of ‘Independent Means’, Henry Hellier, aged 25, a printer, George Hitchins a 25 year old schoolmaster and Ann Bowden a 21 year old servant. Clapp’s age is given as 33.

A few weeks later the North Devon Congregational Association meeting at Barnstaple ‘Resolved that Rev. Mr. Clapp of Appledore be received as a Member of this Association.’ [4] It was at the same meeting that the first local evidence of Clapp’s radical view on life became apparent. The minutes record ‘That Mr. Clapp having expressed his determination to attend the approaching Manchester meeting on the Corn Laws It is resolved that Mr. Clapp be appointed as a deputie from the N.D.Association and that after the Appledore people have contributed their part the ministers of the association agree to raise the residue of the Expence.’

The Report of the Conference of Ministers of all denominations on the Corn Laws contains the proceedings of the Manchester meeting when 645 ministers spent four days in August 1841 protesting against the Corn Laws. [5] This was a politically sensitive subject though Clapp, as a dissenter, would naturally have opposed these laws which maintained artificially high bread prices to the detriment of the poor. At this meeting there were two sessions a day, each lasting 4-5 hours, with a wide array of speakers including Richard Cobden MP. Clapp is recorded as seconding a resolution against the Corn Laws which he saw as ‘a great national offence against that Being by whom kings reign, and princes decree justice.’ He backed this up by declaring ‘Let us….speak again for God on behalf of the poor’ – stirring words from a young preacher indeed.

In June of the following year the North Devon Journal carried a small announcement that the Rev. Jerome Clapp of the Independent congregation at Appledore had married a Miss Margaret Jones of Bideford at the Independent chapel in the latter place.[6] His new wife, whose name is variously spelt as Margarette or Marguerite, was the 23 year old Swansea-born daughter of a draper. She is said to have brought a ‘modest’ fortune to her new husband. [7]

According to his son’s autobiography Clapp ‘farmed land at Appledore’.[8] No record of his purchasing land is extant but in 1854 a court case (referred to later) states he was the owner of the ‘Berners’ estate of 20 acres. Under the name ‘Burners’ this was for sale in January 1850 which was presumably when Clapp acquired it. [9] His son, however, says Clapp brought his mother home to a farm ‘after their honeymoon’ so Clapp senior must have purchased a property around 1842. The only other landholding his name is connected with as owner is Milton Farm. This was sold by Clapp in July 1855 and is described then as consisting of 50 acres of ‘very superior Arable, Meadow and Pasture Land….in the highest state of Cultivation, worthy of being styled a Model Farm.’ [10] Accommodation consisted of ‘a newly built Farm House’ with two labourers’ cottages. Interestingly the property included a ‘Tower’ and a ‘Quarry’. The former was Chanter’s Folly built by a rich local shipowner Thomas Chanter in 1841 as a lookout. The latter still exists today just behind the large modern shipbuilding yard in Appledore. Its origin is described later. This mix of ministry and agriculture does not appear to have been that unusual as most dissenting clergy had to find a second income to subsidise their preaching activities – though few perhaps were farmers on quite Clapp’s scale.

One other land holding is accredited to Clapp. In 1857 the Knapp estate was sold and Clapp was listed as tenant of two fields Windmill Field and East Hill which were adjacent to Bloody Corner the traditional spot at which a marauding Viking was killed.[11] Jerome junior in his autobiography claims, with tongue firmly in cheek, that this Viking, whom he calls Clapa, was the ‘Founder of our House’.[12] The Viking is usually referred to as Hubba and his presumed tomb was excavated in September 1841 by an unnamed antiquarian but nothing much of interest found. [13]

The newly married young minister, not content with farming and preaching, had within weeks of his arrival in North Devon become the Secretary of, and Editor for, The Congregational Tract Society which was established to ‘diffuse extremely cheap treatises and tracts on Protestant Dissent.’ [14] At the August 1841 meeting of the North Devon Congregational Association it was noted ‘That the Ministers of this association cordially approve of the principles and plans of the Congregational tract Society, become Member of its corresponding committee and recommend the circulation of its Cheap publications.’ [15] Three different titles from a series of at least 20 have survived among the archives of what is now the Appledore United Reform Church. [16] Number 19 carried the legend ‘Printed by the Society at their Depository, Appledore, Devon.’ and was sold at 3/6 (17p) per 100. A list of officers is given which includes Clapp as ‘Secretary and Editor’. The treasurer was James Haycroft of Bideford who was helped by a six man Publication Committee and a six man General Committee. One assumes that the printer Henry Hellier listed as living in Clapp’s house in the 1841 Census was employed in producing these tracts. Where the printing press came from is a puzzle as at this date in North Devon such machines were very rare. The Society does not seem to have made much headway amongst the numerous sects of early Victorian Britain or even within Devon.

Clapp’s address on Number 19 in the series is given as Odun House, Appledore which places its publication as somewhere around December 1847 as, in that month, the North Devon Journal notes the birth of a daughter to the Clapps and gives their address as the imposing Odun House. [17] This building was one of the grander houses in the village having eight bedrooms, and again indicates Clapp’s wealth. It still exists today and now houses the Appledore Maritime Museum. Whether the house was rented or purchased is not clear but on Clapp’s removal in 1856 the house and three adjoining cottages were put up for sale so perhaps his wife’s money had been used to buy the freehold. [18]

Clapp was not content to just publicise his views in the form of pamphlets. He had ‘a natural and forceful flair for public speaking’ – a flair often reported on in the North Devon Journal which itself was run by a Methodist family and thus presumably was sympathetic to dissenters in general. [19] Further evidence of Clapp’s politics came in May 1843 when he spoke at a public meeting in Barnstaple Guildhall called to promote the repeal of the Corn Laws. [20] He moved the vote of thanks to the representatives of the National Anti-Corn Law League ‘for their exertions to procure a repeal of the corn laws.’ His speech was fairly outspoken – as when he said of the League, ‘They had looked upon the distresses of the country – they beheld its energies crippled, its commercial and manufacturing interests depressed, and its mechanics and their families huddled together in hovels unfit for human habitation – unemployed and starving: and for their fraternal regard they deserved our honour, that they came forth to the help of the poor – to the help of the poor against the oppressor.’

He then widened the discussion by going on to attack two ‘solutions’ to the problem of unemployment that some had advocated – machine breaking or emigration. He himself was strongly in favour of mechanisation, indeed he said ‘Let machinery be multiplied’ as this could only generate extra wealth for all. As to emigration he had, on the previous Sunday, preached to about 400 on the deck of an emigrant ship about to cross the Atlantic from Appledore. The tears he had seen shed by these poor people forced to leave the country of their birth through sheer poverty only made him more determined to see the Corn Laws abolished and food made cheaper. He sat down, as the report notes, to ‘loud and long continued cheers.’ A month later Clapp addressed a meeting in Bideford’s Wesleyan chapel protesting about the clauses in a Factory Bill that dealt with the compulsory education of young workers and the perceived bias in the bill towards Church of England teachings. [21]

In August 1843 Clapp’s 14 year old nephew Arthur Shorland of London ‘here on a visit to his grandmother’ was staying with his uncle when he decided to go swimming in the Torridge. Sadly he drowned and Clapp ‘who was much affected’ officiated at the burial which, poignantly, was the first interment at the cemetery newly opened by the Appledore Independents – though where this was is uncertain. [22]

Occasional references over the next few months show Clapp preaching in Appledore or addressing public meetings. In February 1844, for example, Clapp chaired a meeting in Bideford where two ministers from Edinburgh and London came to appeal for funds for building ‘new churches for the Free Church Secession in Scotland’.[23] Clapp’s speech was described as ‘excellent’ and presumably this helped raise the sum of £6 collected from his listeners.

A more unusual meeting was held in March 1844 which was a display of the then popular subject of ‘Mesmerism’.[24] Presented by a Mr. Davey at the rather odd venue of the Appledore Bethel it doesn’t seem to have made much impression on the hard-headed seamen of the village. Davey made various excuses for this failure and Clapp invited him ‘to attend at his library the following morning, where he should find a candid audience without heat, or noise, or cold, or laughter.’ Davey did attend and tried to ‘mesmerise’ three boys but again failed and Clapp apparently became so worried at this ‘system which had driven some into a madhouse and others into a grave’ that he gave a lecture in his chapel denouncing the whole thing. This included ‘some striking facts which had come under his own observation when studying anatomy in London’ which suggests another strand to Clapp’s life.

To drive the point home Clapp held a public meeting in Appledore a few days later to discuss the following strongly worded resolution ‘That this meeting, after giving the subject the closest attention, avow their belief that the principles of mesmerism are utterly false, and the practice of it both physically and morally dangerous, and that all the results of mesmeric manipulation may be easily accounted for on physical grounds alone.’ Davey wrote to the Journal defending himself and attacking Clapp accusing him amongst other things of ‘barefaced duplicity’. [25] This sparked a flurry of letters both for and against both mesmerism and Clapp with the minister being charged with ‘sarcastic irony’ and of having hired the ‘Cryer’ of Appledore to spread falsehoods about Davey. [26] Davey, however, came off worst in these exchanges and no further references to mesmerism in Appledore have been found.

In April 1844 the North Devon Congregational Association meeting at Chulmleigh appointed Clapp ‘as representative of this association at the Meeting of the Anti-State Church conference’ although whether Clapp actually attended or not is unknown. [27] Also at this meeting Clapp was asked, along with two others, to preach to a newly formed congregation at Hartland.

May 1845 saw the birth of a daughter named Paulina or Pauline Deodata to Jerome and Margaret, the first of four children. [28] If Clapp’s family was developing so was the village of Appledore. In September 1845 a new quay was constructed by the leading local merchant Thomas Chanter and Clapp was one of those who addressed the enthusiastic crowds at the opening ceremony. [29] A few weeks later, however, a long-simmering problem in the village came to a head. Apparently in 1808 a legacy had been used to purchase £100 worth of ‘South Sea Annuities’ with the income from them being paid to the ‘Appledore Meeting’ to help provide an income for the minister. In March 1842 new trustees were appointed at the prompting of Mrs. Rooke a daughter of the original donor though the income continued to be paid to Clapp. [30] In December 1845 a letter from Miles Prance to the Bideford solicitor and prominent dissenter James Rooker noted that Mrs. Rooke was ‘feeling rather weaker’ and was ‘very desirous of settling at once all her worldly affairs.’ As Prance went on to delicately express it the reading of her will ‘may possibly occasion great inconvenience and surprise to the parties interested in the £100 Trust Money now standing in her Name.’ It was then discovered that Mrs. Rooke didn’t actually have the power to alter her mother’s bequest and nothing seems to have happened until September 1854 when the choice of new trustees lead to a violent confrontation and a major schism in Clapp’s congregation. It is worth noting that Clapp at this time clearly had the support of his fellow ministers as in the minutes of the North Devon Congregational Association for 3 June 1846 it was recorded that he, along with five others, were requested to form a sub-committee ‘to revise the rules of this Association.’ [31]

No references to Clapp have been found between the opening of the new quay and June 1847 when the bitterly disputed Education Act was being discussed in Parliament. A meeting was held of the non-conformist ministers in North Devon where a motion was passed, with Clapp as seconder, requesting all dissenters not to vote for any Parliamentary candidates who supported the passage of the Act. [32] The minutes of the meeting note ‘That an address to the dissenting electors of N.D. explaining of the course recommended in the preceding resolution be prepared by the Rev. J. Clapp and submitted previous to publication to a sub committee composed of Rev. Kent, Thomson, Clapp & the Secretary.’ [33]

In December of the same year Margaret Clapp gave birth to a second daughter. [34] This child was given the odd names of Blandina Dominica whilst the announcement of the birth gives the family’s address as Odun House.

In April 1848 he was invited to address the 3rd AGM of the Bideford and North Devon Building Association held in the Wesleyan school room in Bideford. [35] This group had been formed to allow working men and small traders to borrow money in order to buy their own houses. It still continues today as a constituent part of the Portman Building Society.

This year also saw Clapp travelling overseas to the Brussels Peace Conference in September. Following the ‘Year of Revolution’ of 1848, when Europe erupted in a series of revolutions, locally based Peace Societies were either formed or re-invigorated in many countries. The first international meeting had been held in 1843 in London to be followed 5 years later by the Brussels meeting. Clapp was one of a party 150 strong from Britain. [36] A fellow delegate was James Passmore Edwards who came from Cornwall and later became MP for Salisbury. In his autobiography Edwards wrote, ‘The Brussels Congress was a success. It received the active support of the Belgian Prime Minister, the patronising smile of the Belgian King, a considerable share of public attention, and the good wishes of the lovers of mankind everywhere. That Peace Conference, though it encountered opposition, and got pelted with sneers, was historic, as it was the first of its kind, and it sowed seed which has since germinated, and from which may now be seen the prospect of an international harvest.’ [37] In January a meeting was held in the Barnstaple Guildhall where Clapp and Edmund Fry, another of the British delegates, explained the decisions taken by the Congress. Clapp ended his speech with a ringing call reported verbatim in the Journal ‘Let the present generation profit by the follies of the past. Let the future mark no such crime – no such madness. Let theirs be the high and holy satisfaction of establishing a purer law for the government of the nations – a law in which honour, honesty, morality, humanity, and religion, would alike concur – the law of national arbitration in national wrongs.(Cheers)’ [38]

Another Congress was held in Paris the following year and Clapp seems to have attended this as well – though on this occasion he was accompanied by E. M. White a Bideford builder and one-time Mayor. In November 1849 the Journal carried an account of a public meeting held in Bideford by Clapp for ‘explaining and advocating the Principles of the Peace Society, and of giving some account of the late assembling of the Peace Congress at Paris.’ [39]

One wonders whether all this activity overtaxed Clapp as in October 1850 he was excusing himself from a meeting of North Devon Congregational ministers ‘on account of illness.’ [40] The lack of public notices concerning Clapp over the next few months suggests he was taking life more easily. In March 1851 the census enumerator gives us a glimpse of his family even if Clapp was away from home on census night. [41] His 32 year old wife is there with Pauline and Blandina. Also present was Margaret’s older sister Francis (sic) Tucker Jones plus four servants including a governess, cook and maid. Clearly the Rev. Clapp was not a poor clergyman. Indeed, in August 1851 we find him spending £250 on the purchase of two houses in Bude Street, Appledore from Joshua Williams. [42]

Clapp’s ill health that had been noted earlier seems to have got worse and lead to a major change in his life if we are to judge from an entry in the minutes of the North Devon Congregational Association. This notes a letter apologising for his non-attendance with the words ‘Also from Mr. Clapp excusing his absence on account of his no longer sustaining the Pastoral Relations with the church at Appledore.’ [43] He may have stopped his active ministry but he continued to attend the meetings of the Association.

Clapp’s wealth and illness unfortunately seems to have attracted some professional fraudsters. In December 1851 the Journal carried a long report on a projected rail link to Bideford in the middle of which occurred the following, ‘from what we have seen at Hupplestone, and from what we have heard, we are warranted in predicting that the Bidefordians may be awoke one day by the startling announcement that an Eldorado has been discovered in their own locality. Suffice to say, that a drift has been made, and that tin, copper and lead, have been found, of which more next week.’ [44] Hupplestone, or Hubbastone as it is known today, was owned by Clapp and he presumably had been impressed by what the miners had told him existed on his land. The Journal carried its promised further report two weeks later on ‘The Mine at Hupplestone’ which again was very optimistic in tone, ‘The reports from the above are still very encouraging. In the words of those engaged, they never saw a speculation looking more kindly. We congratulate the Rev.

Jerome Clapp, the owner of the land, on his very good fortune; and trust that such a mine will be discovered, as shall not only benefit the proprietors of the soil and company engaged, but the neighbourhood generally.’ [45] Sadly this is the last positive notice of the mine, indeed in October 1852 the Journal carried two sentences which tell us all we need to know about the operation, ‘The works at the Silver and Lead Mine at Ubbastone, in this place, are at the present suspended. They will be again resumed, we hear, as soon as a company can be formed.’ [46] In his autobiography Clapp’s son writes laconically of his father’s action over this fraudulent mine by saying that he ‘started a stone quarry’. This may well have been a face-saving device or perhaps Jerome junior was never told the truth. A 1904 article on the history of Appledore records that ‘The entrance to the mine was from the beach, and was tunnelled for some distance under the field where the tower of “Chanters Folly” now stands, and then a shaft sunk.’ [47] The article also refers to the ‘Mine Captain’ fraudulently ‘salting’ the shaft with real silver ore to convince Clapp to carry on work.

The 1852 references actually begin in January when Clapp organised a temperance meeting at Appledore at which the principal speaker was F. W. Kellogg from the USA. [48] The Kellogg family were famed advocates of temperance and one of them later invented the famous breakfast cereal though how this Appledore visitor was related to the famous inventor is unclear. This new burst of activity suggests Clapp’s illness was improving but perhaps not enough for him to restart his ministry in Appledore. In the same issue of the North Devon Journal carrying a report of this meeting is an odd little item to the effect that Clapp’s dog called, grandly, Canino Fidel, had died. [49] This apparently was cheering news to the local women and children to whom the dog had been a ‘terror’ for many years.

On June 1 1852 a Wesleyan Reform meeting was held at the Independent Meeting House (the present-day Lavington chapel) in Bideford. [50] Clapp as a Congregationalist seems to have been invited along to be a neutral chairman and keep order between two groups of disputing Methodists. This sounded innocuous enough but religious passions ran high in mid-nineteenth century England and the actions of Thomas Evans ‘late Mayor of Bideford’ (in 1849 and 1850) led to Clapp publishing the text of ‘A Correspondence’ between him and the local councillor. [51] It was published by ‘The Committee of the Bideford Wesleyan Reform Association’ and although no printer is listed we can assume it came from Clapp’s own press. The price was a nominal ‘One Halfpenny’ – evidently Clapp was hoping for a wide sale.

The introduction notes that Clapp had to deal with two disruptive members of the audience at the meeting. The first, John How, ‘had ‘utter’d a malignant fabrication against the Rev Gentleman [Clapp] before the teachers of the Sunday School’ which he later denied and on ‘being invited to meet those who heard him he refused; preferring to write a series of letters, which the Committee for their Chairman’s sake hope may soon be published.’ The second was Evans who at the meeting caused ‘the greatest disturbance by his perverse and disorderly conduct’. Two days after the meeting he wrote to Clapp and this letter, along with the latter’s reply, formed the text of the pamphlet. Both How and Evans were said to be ‘advocates of Conference Methodism’ i.e. Methodists who were willing to accept centralised control – as opposed to local independence. As part of this they supported the exclusion of a Mr. Dunn from the ministry even though he had worked throughout Britain for the church for 35 years. The majority of Bideford dissenters seem to have disagreed with his suspension and let their feelings be known at the meeting.

The kernel of Evans’ complaint in his letter was that Clapp had not been neutral but instead had chosen to throw his weight behind Dunn’s supporters. Evans at one point wrote rhetorically, ‘I would ask whether the antecedents of the Rev. Jerome Clapp, are such to show that he is a man to whom we may look, as a competent authority, to lecture the Wesleyan community on matters of Church Government.’ As if this wasn’t enough, he went on to question the success of Clapp’s ministry. After pointing out that ‘I have known something of the Independent Church and its members at Appledore for the last 30 years’ he went on to ask ‘for proofs of the flourishing state of your Church after many years of your Ministerial labours among them.’

Clapp’s reply was three times as long as Evans’ letter and dwelt in detail on what had happened at the meeting. He notes, for example, that Evans was hissed by the audience, refused to answer questions and overwhelmingly lost the eventual vote. In passing Clapp also attacked ‘Mr. Avery’ who, from internal evidence, was probably William Avery, the then Mayor of Barnstaple and editor of the North Devon Journal, who was also present at the meeting. The letter ended with a ringing series of phrases; ‘I thank God I am an Independent and not a Wesleyan Minister. And let me devoutly thank God also, that I am not a Bideford labourer wanting Methodist work; nor a Bideford mechanic seeking Methodist employ; nor a Bideford tradesman observing Methodist custom, upon whom more persons (let me hope that are but few) of the Bideford Conference party might turn the screw in the spirit developed in the late meeting.’ I have been unable to trace any further repercussions of this exchange of letters and, though such religious disagreements were common, Clapp’s conflict with such prominent adversaries can’t have endeared him to powerful elements in the local population.

In answer to Evans’ mocking question re the success or otherwise of Clapp’s ministry he vehemently replied, ‘all the disasters and contentions which have arisen here and which you in the spirit of the Evil One seem to gloat over, have occurred only since, and only because I closed my ministry, and through ill health terminated that pastoral relation which for 10 years secured the very highest approval of those, who seized the occasion of its close to risk so much evil, (I hope not by your encouragement, though perhaps for the sake of drawing them to Methodism you became a consenting party) and exhibited so much evil, in an ungodly struggle (like your own) for unscriptural and dangerous power.’ Whether Clapp ever resumed active proselytising in Appledore is hard to say as the records covering his period in post are missing – presumably removed by Clapp himself when he eventually left the village. This illness could also explain some later events connected to the endowment of the Appledore Independent chapel.

In September 1852 the Journal printed a letter from the Appledore clergyman concerning the proposed railway line between Bideford and Barnstaple. [52] Given Clapp’s progressive views we should not be surprised to find him advocating its rapid construction. Intriguingly he ends his letter by quoting the words of ‘Mr. Evans’ (presumably the Bideford Mayor with whom he had had the public disagreement) to the effect that ‘the town that consents to be without a railway, consents so far to its obscurity and ruin.’ Another indication of both his interest in railways, and the wealth his wife brought him, comes in October 1852 when, in an advertisement on the front page of the Journal seeking investors into the proposed Bideford-Okehampton railway, Clapp’s name is listed in the ‘Committee of Shareholders’. [53]

Again in September 1852 Clapp spoke at a meeting in Bideford called to discuss moves to persuade local traders to close early for half a day each week. [54] Clapp took the position that such free time was essential to the shop assistants. He actually hoped they would use it to educate themselves – a need he illustrated by an odd story; ‘He was at this moment deprived of the services of a valuable servant because he would not sleep in a room which he said was haunted by a ghost. He had talked with him and tried to shame him out of it, but it was of no use.’ He went on to suggest two positive moves – that ‘ladies’ should boycott shops that stayed open late and that a committee be established to implement an early closing agreement in the town. The latter was carried and indeed early closing became the norm in Bideford.

This was the same month that Clapp’s silver mine finally faded away and speculation that he lost heavily in this debacle is hinted at by an action brought against the clergyman in February 1853 in the Bideford County Court. [55] A Mr. Clibbett sued Clapp over an unpaid account for £2.5.9 Clapp denied he owed the money saying the bill was a fabrication and that in any case some of it extended over 12 years and was thus ruled out by the statute of limitations. He went on to claim that the case had only been brought owing to ‘an unpleasantness that had occurred between them’ though what this was is left unstated. The judge seemed to accept these points but still ordered Clapp to pay 3/9 to Clibbett.

Only a week later Clapp was present at a public meeting in Appledore to consider the proposal of local merchant and shipowner William Yeo to build a dry dock in the village. [56] Clapp we read ‘moved a resolution, expressive of the most cordial concurrence in Mr. Yeo’s public spirited proposal which being seconded by Mr. Lake, was carried by acclamation.’ The dock was completed in 1856

A month later the Journal published a letter from Clapp on the Bideford British School and the ‘Voluntary Principle’ of support for such nonconformist-run schools. [57] Clapp championed this and denounced the fact that fund raising sermons in ‘two highly respectable and important congregations’ in Bideford only raised a paltry £3 and that evidently the school had to be sustained by Government grants. A reply came the following week from Bideford solicitor W. S. Rooker which reckoned Clapp’s complaint rested an ‘an entire mistake’ – one ‘which is exceedingly surprising from his well-known intelligent discrimination and large information.’ At some length Rooker spelt out the finances of the school and the inadequacy of Government funding though he does not address the point about the miniscule collection. Clapp chose not to reply but clearly he had upset Rooker and his fellow school governors. Clapp’s views were further challenged at a meeting of the Bideford Mutual Improvement Society which, although mentioning the ‘defunct state of the British Schools in the neighbourhood’ reckoned reliance on State payments to keep such schools going was perfectly acceptable to nonconformists. [58]

After this concentrated burst of publicity we have to wait until December 1853 to find Clapp again making news. [59] In this month he chaired ‘A working men’s demonstration in favour of Total Abstinence’ in the Bideford Mansion House. The meeting began with Clapp declaring ‘that if ever he felt proud in his life it was on that occasion, surrounded as he was by a company of working men, who were there to testify as to the benefits they had received from abstinence principles.’ Interestingly the Journal chose to report Clapp’s speech at length but ignored ‘The powerful arguments adduced’ in favour of teetotalism by the working men present – a reflection perhaps of its perceived class of readers. A further temperance meeting followed in February 1854 in Appledore where Clapp was ‘unanimously called to take the chair.’ [60] He then introduced six speakers including Edward Capern (Bideford’s ‘postman poet’) and a Mr. Thoroughgood who proudly exhibited a ‘handsome watch’ he had purchased by saving ‘the cost of a pint of beer a day’ over 18 months.

The following month saw Clapp lecturing on ‘Anglo-Saxonism’ to the Appledore Mutual Improvement Society. [61] He was, according to the Journal report, ‘listened to with marked attention’ especially when he gave ‘a bird’s eye view of the future’ of England. Sadly what this might have been is left unstated though given Clapp’s dissenting background these would probably have included aspects of social justice and reform. He also appeared at this Society in May 1854 when ‘Poetry’ was the subject under discussion. [62] A month previous to this Clapp was in the news following the discovery of a ‘chalybeate spring’ on his land. [63] This was a flow of water heavily impregnated with iron – and presumably seen as a ‘mineral’ water although there is no indication it was ever used as such.

This was one piece of good news in what was a trying time. In May a meeting of local Congregational ministers at Bideford noted that this was their first meeting for two years owing to ‘the peculiar state of the churches’ in that Bideford, Ilfracombe, Appledore and Chulmleigh had no pastors and the Barnstaple minister was very ill. [64] In order to reinvigorate the cause a six man committee was set up ‘to visit Appledore and confer with the friends upon the present state of things there & to arrange for holding the Autumnal meeting at Appledore.’ This meeting was actually held in Barnstaple – and Clapp attended.

At this time Clapp’s interests were moving away from the church and becoming focused elsewhere. In June 1854 a Mr. Gough, who had achieved fame as a public speaker on the evils of drink, came to Bideford and gave a very well received lecture on the subject. [65] Clapp seems to have been the organiser of a follow-up meeting when about 1000 ‘working men’ came to hear Gough in a large marquee. Clapp took the chair and he ‘congratulated the working men of Bideford on their public spirit.’ This meeting went so well that Clapp organised another at Buckland Brewer near Bideford. Again, a marquee was erected and, surprisingly perhaps, in this very rural area, some 800 people turned up to listen to Clapp and other speakers support the temperance cause. These two meetings can be described as the last high points in Clapp’s career in North Devon; never again was he to have the support of so many.

The decline began in September 1854 when a case ‘which has excited public curiosity’ was heard in the County Magistrates Court in Bideford. [66] Clapp, described unexpectedly as ‘a gentleman of some notoriety in the neighbourhood’, charged both Thomas Cook senior and junior of Appledore with an assault. On the 3rd of September Cook senior, who was ‘a leading member’ of Clapp’s congregation affixed a notice on the chapel door about a meeting to choose new trustees to manage shares and the property of Mrs. Betty White which formed the endowment of the chapel. These shares have been mentioned earlier when new trustees were chosen in 1842. Clapp came by his chapel with his wife, two children and niece, saw the notice – and ripped it down. The older Cook then, according to Clapp, ‘took hold of my neckcloth, and pressed his knuckles into my neck, producing a painful sense of strangulation.’ Margaret Clapp then ran to them and exclaimed, ‘You dare to strike him.’ Cook ignored her and according to the clergyman’s evidence said ‘Hell was too good for me.’ At this point Cook junior had arrived and ‘placed his back against the wall on which the notice had been affixed, took off his gloves, squared his fists in a threatening manner, and said “Shall I strike him father?” ‘His father replied ‘I am man enough for that, and for two pins I would kick him down the steps.’ Another younger Cook then turned up and began shouting ‘Go it father, go it father!’ This account formed the basis of Clapp’s evidence and he was supported by James Clannan the sexton of the chapel who was heard to mutter that ‘it was a rough piece of business altogether.’ Two other witnesses appeared including Jane Turner who worked for Clapp. She had heard one of the Cooks call her employer ‘a d__n rogue, and that hell was too good for him.’

The Cook’s defence was summed up in a paper which their solicitor read to the court ‘detailing some circumstances connected with Mr.Clapp’s relation to the Independent Congregation, and the appointment of trustees’ which concluded with the statement that ‘a meeting we want and a meeting we will have.’ They called James Kiell as a witness who recounted how he had seen Clapp pull the notice down ‘like an infuriated demon’. The Cooks had not assaulted the minister and he had heard no abusive language used.

Faced with such directly contradictory evidence the magistrates were clearly in some difficulties. They only took a short while, however, to return the judgement. They reckoned Clapp ‘had used strong provocation in pulling down the paper, and that Mr. Cook had used violence which he had no right to do.’ They, therefore fined both parties a risible 6d each and made each responsible for their own costs in the case. Unfortunately for the historian nowhere is it stated what the underlying facts of the case were; was it a simple disagreement over who had the right to call a meeting, was it about the choice of trustees or was it, given the strength of Cook’s denunciations, a case of peculation of the chapel funds? One possibility is that even though Clapp gave up his active ministry around 1850 he was still drawing on the chapel’s endowment funds. At this distance in time it is impossible to discover but whatever it was it began Clapp’s downfall.

Within a few days Clapp’s opponents had moved against him as a report in the Journal shows; ‘Appledore. A public meeting was called on Wednesday last, to be held in the Independent chapel, for the purpose of appointing trustees for that building, and for the property by which it is endowed. Admittance, however, into the chapel for that purpose was refused by the minister; the meeting was, consequently, held in the Bethel, when fourteen persons from this and the neighbouring towns were appointed to act as trustees. The deed is now in course of execution, after which it is to be hoped things will take a more pacific turn, and no more work be made for the magistrates, to the great scandal of all that is good.’ [67] Clearly Cook and his party had circumvented Clapp by completely legal means and in so doing had highlighted the traditionally precarious position of nonconformist ministers when compared to Church of England clergy.

Before Clapp could react, he had to deal with another case when he was summonsed to the County Court, this time as a defendant in a case over trespass. [68] Frederick Thorold rented an estate known as Bidna from the Cawsey family and he complained that Clapp, who owned the neighbouring estate known of Berners, had illegally ‘opened the hedge’ separating their landholdings, put up a stile and cut down an oak tree. The magistrates soon dismissed the case finding in Clapp’s favour and awarding costs against Thorold.

Once this was out of the way Clapp could return to the more pressing matter of the chapel dispute and on 26th September 1854 he called a meeting ‘in opposition to the one held the other week, in the Bethel’ but ‘for the same purpose as the other’ i.e. to choose new trustees. [69] Whereas the first meeting had been open to the public this one was by ticket only. The Rev. S. Kent of Braunton chaired the proceedings which saw the nomination of trustees but, as the Journal noted, ‘what was thought rather extraordinary, they were all persons living out of the neighbourhood’. In addition ‘Constables, it is said, were stationed at the door to prevent the entrance of persons inimical to the proceedings. Lovely.’ This last detail suggests a growing paranoia on the part of poor Clapp. What is certain, however, is that the trustees nominated at this meeting never took up their posts – indeed a set of new trustees were finally appointed in 1856.[70] In the next few months the minister seems to have tried to marshal support. Only a month after the assault case he hosted a 70 strong tea party in the Independent chapel. The Journal noted that ‘The sale of tickets was restricted to the limited accommodation, or many more would have been present’ which strikes one as odd given that the chapel could hold 570 people! [71] After a series of congratulatory speeches ‘the party separated with mutual expressions of gratification.’

That Clapp was under pressure is shown by the minutes of the North Devon Association of Congregational ministers which, in November 1854, records, ‘The subcommittee appointed to visit Appledore having declined presenting any report, Mr. Buckpitt referred to circumstances which satisfied him that Mr. Clapp had met with much unkind and ungenerous treatment from individuals where hostility was as unprincipled as immoderate while the state of affairs at Appledore was as low and deplorable as it well could be. It was resolved after remarks by Mr. Clapp & others to pass to the next resolution.’ [72] For the moment Clapp’s position seemed to be secure if shaky.

In February 1855 Clapp chaired both a temperance meeting in Bideford and a lecture on Chaucer to the Appledore Mutual Improvement Society. [73] In March he gave an extempore lecture on ‘Water’ to the Bideford Mechanics Institute where ‘the interest of a large and respectable audience’ was ‘maintained to the end’. [74] In the same month he led the vote of thanks to a speaker at the Appledore Mutual Improvement Society whilst in April he, along with Edward Capern, was lecturing in Buckland Brewer. [75] To round off a busy 6 months the Journal in June 1855 carried a notice that the Clapp family of ‘Odun House’ had been enlarged by the birth of a son. [76] Named Milton Melancthon either after the poet or his father’s farm, he died aged 6. [77] Given this concentrated burst of activity and a new child it is rather surprising that, only a few weeks later, the Journal carried a large advertisement notifying the public that Milton Farm plus 50 acres of land was to be auctioned in August. [78] The auction, however, was unsuccessful and the property was again put on sale in October although this time it was split into 16 lots. [79]

In October 1855 a small note in the Journal records the re-opening of the Independent Chapel at Appledore ‘after a period of “suspended animation”.’ When a Mr.Haycroft ‘late of Bideford and now of London’, and presumably the same person who had acted as Treasurer to The Congregational Tract Society, preached. [80] Two days later several local Congregational preachers held a service when 200 worshippers turned up. Also, in February 1856 ‘a social Tea Meeting’ was held in the Appledore Bethel where 120 people attended being described as ‘the friends of the Independent Chapel in that place’. They heard two clergymen and three lay people deliver speeches which ‘were expressive of a strong desire for the restoration of that peace and union which had been formerly enjoyed by the Church – but which has of late been interrupted by many unhappy circumstances.’[81] Apparently the entire gathering ‘were cheered with the hope of soon seeing a Minister established among them.’ The North Devon Association of Congregational ministers meeting at North Tawton in November 1855 noted Clapp’s ‘retirement’ and that Messrs.Corke, Peacock and Young had offered to preach ‘the fourth Sabbath in January, February and March [1856] respectively’ so their hopes seem to have been met. [82]

From the above it is clear that sometime between July and October Clapp had precipitately left Appledore with his family. In fact he had gone to Walsall where he altered his name to the grander sounding Jerome Clapp Jerome and carried on preaching in local Congregational chapels – and lost most of what remained of his wife’s fortune in digging coal pits and trying to run an iron foundry. [83] What, however, had prompted his move?

In a series of notes on the history of the Appledore United Reform Church there is a short entry that reads ‘Dark Period. Apparently church full. Jerome Clapp. Fine figure of a man. Intellectual – Scandal.’ [84] In addition The North Devon Congregational Magazine from 1888 [85] printed a short piece on the history of the Appledore chapel which mentioned Clapp ‘during whose ministry a succession of untoward circumstances reduced the cause to a very low ebb, and at last, in 1855 he retired under a very dark cloud, and the chapel was closed for a very short time, the few people who had remained dispersing themselves amongst the other congregations in the town.’ [86]

So what was this ‘scandal’ and ‘very dark cloud’? Clearly Clapp had upset people and there were unanswered questions about aspects of the chapel finances but what brought it to a head? There is, in fact, still an oral tradition in Appledore that Clapp was the father of at least one illegitimate child – reason enough for a rapid departure and a decline in the chapel membership. [87] Whether the story is true or not it is clear that Clapp’s enemies were actively spreading damaging rumours against him. A printed letter dated ‘Walsall, December 26, 1856’ and addressed to ‘J. C. Jerome Esq’ reads, ‘We the undersigned, having thoroughly and carefully investigated the reports which have been so industriously circulated against your moral character, have, by the most abundant and conclusive evidence, proved, to our unanimous satisfaction, that the same are wicked and malicious untruths, originated by base men to gratify private revenge. We therefore take this opportunity of expressing our Christian sympathy with you, under these severe trials, hoping that God, who sees all hearts, will, in his own good time, confound and bring to nought their wicked counsels. This sympathy of ours we would doubly tender, as it is with feelings of great regret we find that certain individuals, from whom, as members of the same church, you ought to have expected Christian help and assistance, have given such ready and willing credence to the slanderous reports of your known enemies.’ The list of 16 signatories is headed by Samuel Stephens ‘Magistrate and Alderman of Walsall’. [88]

It is true that in January 1857 Clapp and 20 others seceded from the Bridge Street Congregational chapel in Walsall and this letter might refer to some long forgotten religious dispute but the reference to ‘moral character’ seems to tie it in with the Appledore story – and the fact that the letter is preserved in the archive of a Bideford organisation suggests it relates to a North Devon event. [89]

Further light is thrown on these events in the minute book of the North Devon Association of Congregational ministers. [90] Meeting at Chulmleigh in April 1857 the 18 men present discussed a letter they had received from Walsall and minuted the following, ‘Letter having been read from Dr. Gordon and the church at Walsall containing certain statements and making certain inquiries relating to Mr. Clapp late Minister at Appledore and a member of this Association but now of Walsall and known there as Jerome C. Jerome Esq.

Also: A copy of the Secretary’s reply and a letter signed E H Holden addressed to several ministers of this Association the object of which appears to be to discredit the reply of the Secretary.’

After discussion the meeting passed the following motion, ‘That this Association approve the letter of their Secretary addressed to the Pastor & church at Walsall under date 29 December last and adopt it as their own. That they deem it the solemn duty of Mr. Clapp to make every effort to disprove the charges so seriously affecting his moral and Christian character, referred to in this correspondence. That in the event of no sufficient steps being taken by Mr. Clapp for the clearance of his character from those charges previous to the next meeting it will be the painful duty of this Association to consider the propriety of removing Mr. Clapp from their fellowship. That copies of these resolutions signed by the Ministers & Delegates present be transmitted to the Church at Walsall and to Mr. Clapp. That this Association desire to convey to the Minister & Church at Walsall the expression of their deep sympathy in the troubles occasioned by Mr. Clapp and their fervent hope that by the overruling Providence of the great Head of the Church what has happened may be followed by a great and lasting blessing.’

Some 7 months later in November 1857 the Association met at Barnstaple and noted that a copy of their resolution regarding Clapp had been sent to him and the Walsall church. Clapp had not replied but the Walsall congregation had sent their ‘resolution’ which was copied into the North Devon records. It reads, ‘Resolution passed unanimously at a Meeting of the Congregational Church Walsall October 1 1857 with a request that it be transmitted to the Secretary of the N. Devon Association of Congregational Ministers. Resolved unanimously That the Church feels truly thankful to the N. Devon Assoc. of Congregational Ministers for their kind expressions of sympathy in reference to the severe trial of principle which this church has been subjected by the conduct of the Rev. Jerome Clapp and trusts the Great Head of the church may overrule these trials for his own glory and the ultimate good of his Church; and while expressing this hope this Church would also express the assurance that as they have done their duty irrespective of consequences confiding in God and vindicating the principle of a pure fellowship, the Congreg. Association of Devon will not shrink from them, but take such steps in due course as a regard to their own Association as Ministers of Christ and the interests of the cause of the divine Lord so manifestly demands.’ It is signed by Pastor A.Gordon and five deacons.

When this was read to the North Devon meeting it gave rise to ‘anxious deliberation’ – so much so that ‘It was at length suggested by the Secretary that in so painful a case Special prayer should now be offered seeking Divine Guidance in this matter whereupon Revd. Mr. Whiting offered solemn prayer to God.’ This seems to have worked as the group decided that Clapp, having not replied to their letter ‘has thereby deprived himself of the fraternal confidence of the Associated Churches and brethren.’ More tellingly they went on to add ‘That regarding it to be their imperative duty to countenance in the ministry no man whose moral and religious character is not free from all reasonable suspicion this Association is unhappily compelled to carry out the Resolution IX of last meeting.’ Copies of this decision were then sent to Clapp and the church at Walsall.

The next Association meeting was held at Appledore on 28 April 1858 with the Rev. Edward Hipwood, Clapp’s replacement, in the chair. This heard, and minuted, a letter from Walsall thanking the North Devon churches for their ‘fidelity’ in expelling Clapp.

On this inconclusive note Clapp passes from North Devon history. There is an odd reference in his wife’s diary to him returning to Appledore in August 1866 for a week – possibly to tie up some loose financial ends? Additionally his wife and son visited Appledore in July 1868 but nothing is known of this other than that various locals welcomed them and seemed to show genuine warmth to Mrs. Clapp [92] In conclusion Clapp’s time in Devon can best be described as ‘interesting’ and ‘varied’ Those wishing to follow Clapp’s life up to his death in 1871 are referred to a paper by Alan Argent. [93] It is worth noting, however, that Joseph Connolly in his introduction to a 1992 edition of Jerome K. Jerome’s autobiography highlights the son’s curiously intense efforts to retain his family’s privacy – especially with regard to his stepdaughter and natural daughter along with his own marriage to a divorcee. [94] One wonders if this ‘intensely private man’ felt further burdened by his father’s secrets? Connolly in a postscript ends with the comment ‘If Jerome had secrets, they have all been kept.’ The article you have just read perhaps draws back the veil to a certain extent.

Peter Christie

APPENDIX 1

Each measures 75 mm by 120 mm and are printed on thin paper. No.1 is entitled ‘An address on the duty of diffusing Congregational Principles’, consists of 12 pages and was sold at the nominal price of 1/6 per hundred. No author is given but the Rev.Jerome Clapp of Marine Parade, Appledore is given as the publisher. The author states in the preface that ‘Infidelity taking advantage of the times is using the Printing Press to overthrow the pulpit, and High Churchism is employing it also to rivet the chains of superstition upon prostrate conscience. To those it must not be left. True piety must engage it in her service to enlighten and to bless the world.’ No.4 in the series carried the title ‘The Voluntary System explained in a Letter to the Lord High Chancellor of England.’ Again no author is given and it is the same size and price as No.1 The booklet exists in two different coloured covers. The third survival is numbered 19 and address ‘The Practical Evils resulting from the union of Church and State.’ The author is given as Edward Miall who took 24 pages to explain his argument. Dr Alison Grant believes the printing press was

It is also worth noting that Clapp apparently produced other material on his press. A letter to the Western Daily Mercury which was reprinted in the North Devon Journal reads, ‘An Appledore correspondent writes – In your issue of the 22nd mention is made of the Appledore hymn book, published by the late Rev.Jerome Clapp. It is quite true, as a reader of the British Weekly says, the hymn book was well known and widely used. About the same time, too, Mr.Clapp printed and published a book of tunes for the hymns, many of them being named after members of his family or members of his congregation.’ [91]

- Jerome K.Jerome – A Critical Biographyby Joseph Connolly. (Orbis 1982) A search of the Register of the Scholars Admitted to Merchant Taylors’ School from A.D.1562 to 1874 edited by C.Robinson (1882-3) reveals no Clapp – personal communication from Frank Rodgers

- North Devon Journal 20.8.1840 3a [Hereafter NDJ]

- 1841 Census – Appledore, NDRO

- NDRO B560/1

- Report of the Conference of Ministers of all denominations on the Corn Laws 1841, Manchester – NDRO B151 add/42

- NDJ 9.6.1842

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome. (London 1926/1992) The son calls his grandfather a solicitor but he appears as a draper on the wedding certificate – personal communication from Frank Rodgers

- My Life and Times

- NDJ 31.1.1850 1b

- NDJ 12.7.1855 4c; 26.7.1855 4c; 25.10.1855 4c

- NDJ 29.10.1857 1a

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992)

- NDJ 23.9.1841 3d

- NDRO B151 add/28/32

- NDRO B560/1

- NDRO B151 add/28/29-32

- NDJ 16.12.1847 3f

- NDJ 31.7.1856 1a

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992) + Journal’s 175th Anniversary by P.Christie in NDJ 1.7.1999 – 29.7.1999

- NDJ 4.5.1843 2f-3e

- NDJ 8.6.1843 3c

- NDJ 31.8.1843 3b

- NDJ 15.2.1844 3c; 22.2.1844 3e

- NDJ 28.3.1844 3a

- NDJ 4.4.1844 3b-c

- NDJ 11.4.1844 4b-d

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 15.5.1845 3a

- NDJ 18.9.1845 2g

- NDRO B151 add 48/22

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 10.6.1847 2c

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 16.12.1847 3f

- NDJ 27.4.1884 3d

- NDJ 28.12.1848 3a

- A Few Footprintsby John Edwards (Privately published 1905)

- NDJ 4.1.1849 3b-c

- NDJ 4.1.1849 3b-c; 1.11.1849 5c

- NDRO B560/1

- 1851 Census Appledore – NDRO

- Alison Grant – personal communication

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 18.12.1851 5a

- NDJ 25.12.1851 8b

- NDJ 21.10.1852 8a

- Bideford Gazette 17.5.1904

- NDJ 15.1.1852 5c

- NDJ 15.1.1852 5d

- NDJ 3.6.1852 8b-d

- A Correspondence between Thomas Evans Esq (late Mayor) of Bideford and the Rev.Jerome Clapp of Appledore respecting the late public meeting on Wesleyan reform held at the Independent Meeting House, Bideford; June 1st1852. No printer stated. Copy held in NDRO.

- NDJ 2.9.1852 6d

- NDJ 14.10.1852 1a

- NDJ 9.9.1852 8b-c

- NDJ 17.2.1853 8c

- NDJ 24.2.1853 8b

- NDJ 3.3.1853 6b

- NDJ 17.3.1853 8a

- NDJ 15.12.1853 8a-b

- NDJ 9.2.1854 8b

- NDJ 9.3.1854 8a

- NDJ 18.5.1854 8a

- NDJ 20.4.1854 8b

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 22.6.1854 8b

- NDJ 7.9.1854 8b-c

- NDJ 14.9.1854 8a

- NDJ 14.9.1854 3b

- NDJ 28.9.1854 8b

- NDRO B151 add 48/22

- NDJ 12.10.1854 8b

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 8.2.1855 5d; 22.2.1855 5e

- NDJ 1.3.1855 5d

- NDJ 5.4.1855 7e

- NDJ 14.6.1855 5e

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992)

- NDJ 12.7.1855 4c; 26.7.1855 4c

- NDJ 25.10.1855 4c

- NDJ 11.10.1855 8b

- Bideford Gazette 5.2.1856 1a

- NDRO B560/1

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992)

- NDRO B151 add 28/6

- The North Devon Congregational Magazine 1888

- NDRO B151 add 28/17

- Alison Grant – personal communication

- NDRO B66B/1/1

- Yates, Librarian of Walsall Local History Centre – personal communication

- NDRO B560/1

- NDJ 25.10.1900 8b

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992). Frank Rodgers of Guatemala who now owns Marguerite Clapp’s diary kindly supplied this entry from it which refers to Marguerite’s trip; ‘1868, July 18. This morning we start to pay our long talked of visit to Devon and altho’ we anticipated much pleasure I had no idea realysing half the kind attention and reception I and the dear children received. They seemed to remember all my acts of kindness which I had long ago forgotten and quite overwhelmed me with their love and affection. We enjoyed ourselves excessively. My visit has been to me like the refreshing rain after a long and dreary drought. Papa met us and we all came home safe again tho’ we left Jerome behind at Salisbury. They forwarded him by express and we met on the Platform.’

- Alan ArgentThe Tale of an Idle Fellow, Jerome K.Jerome in Congregational History Circle Vol.3 no.4 pp.18-30 1996

- My Life and Timesby Jerome K.Jerome (London 1926/1992)

Peter Christie is a retired teacher whose articles on Bideford life appear weekly in the North Devon Journal – where he has also published the ‘Yesteryear’ photographs for the last 15 years. He was the Reviews Editor of The Local Historian magazine (published by the British Association for Local History) for 12 years and a long time Open University lecturer. He is the longest serving councillor on both Torridge District and Bideford town councils and has been Chairman of the former as well as serving as Mayor of Bideford 4 times and chairman of the Bideford Bridge Trust on 3 occasions. He is also a trustee of the North Devon Museum Trust and is chairman of the North Devon Athenaeum. He has published thirty eight books.