Jerome The Man

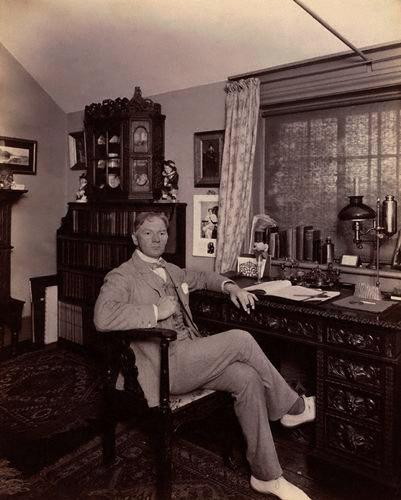

Jerome Klapka Jerome, best known as the author of Three Men in a Boat, one of the great comic masterpieces of the English language, was born in Walsall, Staffordshire, on 2nd May 1859, the youngest of four children.

Jerome left school at fourteen and worked variously as a clerk, a hack journalist, an actor (‘I have played every part in Hamlet except Ophelia’) and a schoolmaster. His first book On the Stage – and Off was published in 1885 and this was followed by numerous plays, books and magazine articles.

In 1927, one year after writing his autobiography My life and Times, he was made a Freeman of the Borough of Walsall. He died later the same year and is buried in Ewelme in Oxfordshire.

Though a relaxed, urbane man, Jerome was a relentless explorer of new ideas and experiences. He travelled widely throughout Europe, was a pioneer of skiing in the Alps and visited Russia and America several times. He was a prolific writer whose work has been translated into many foreign languages, but as Jerome himself said: “It is as the author of ‘Three Men in a Boat’ that the public persists in remembering me.”

Jerome’s Life

Jerome was still a struggling unknown when he confided to his friend George Wingrave that he had four ambitions in life:

- To edit a successful journal.

- To write a successful play.

- To write a successful book.

- To become a Member of Parliament.

Only the last eluded him. Not a bad achievement, especially when you consider Jerome’s background, one that did not exactly augur success, certainly not in a theatrical or literary career, let alone as the author of a comic masterpiece that has become among the most enduring and endearing books in the English language.

Jerome’s background is interesting and quite unusual. And then there’s that middle name – Jerome KLAPKA Jerome. But that wasn’t the name he was christened with. And the story put about as to how he came to be called Jerome Klapka Jerome has proved to be palpably untrue.

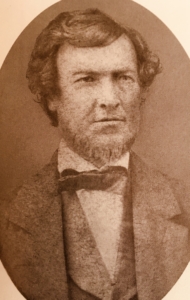

Jerome’s father’s name was Jerome Clapp. He was born in London in 1807. He trained to be an architect but spent most of his life as a Nonconformist minister. He married a Welsh girl and went to live in Appledore in Devon. Parson Clapp, as he was known, gained a reputation as an exceptionally eloquent preacher, very much in the fire and brimstone tradition. He designed and built his own large house, did a little farming and tried his hand, unsuccessfully, at mining silver ore on his land. Financially, the family was well-off, even prosperous.

He fathered two daughters (with the exotic names Paulina Deodata Clapp and Blandina Domenica Clapp) and a son, Milton Melancthon Clapp, who was born in 1855 and died of the croup aged six.

Then in 1855 the Clapp family suddenly left Appledore – under a bit of a cloud. The Rev. Clapp had made himself extremely unpopular with the locals… and there were rumours of an illegitimate child (see the link to The Rev. Jerome Clapp in Appledore by Peter Christie). Clapp moved the family up to Walsall where he changed his name to Jerome Clapp Jerome – and became known as the Rev Jerome. He built his own chapel, and again attracted a large and faithful following for his preaching. So it was into this unorthodox and highly-religious family that Jerome Junior was born on 2nd May 1859. His birth certificate clearly states that he was christened Jerome Clapp Jerome – the same as his father’s new name. To save confusion, young Jerome was known in the family as Luther.

The story you will read in any reference book, however, is that he was christened Jerome Klapka Jerome, and that he was named after General George Klapka, the young hero of the Hungarian War of Independence of the 1840s who was exiled in London. Needing somewhere quiet to write his memoirs, so the story went, Klapka landed up in the Jerome household and became a family friend. Jerome Junior was born, it was said, while the General was visiting the family. The source for this fiction is uncertain, but fiction it most certainly is.

Following research by one of the Society’s patrons, the late Frank Rodgers, it has been established that Jerome’s mother died on 20 July 1875, when Jerome was 15. The death certificate notes “J.C. Jerome, son, present at the death.” ‘Note the middle initial,’ says Rodgers. ‘That rather puts paid to the notion of his being named in honour of General Klapka!… Since Klapka’s memoirs were published in 1850, if Jerome Senior wished to honour him, wouldn’t it have been more logical to do so when his older son Milton was born? My guess is that just as his father adopted the surname Jerome, presumably because “Parson Clapp” didn’t sound too good, and as his father’s nephews who were doctors, with even greater reason abandoned their style of “Doctor Clapp” and substituted “Woodforde”, I think that when he began to write, Jerome looked for something with a bit more glamour than his real middle name.’ However, we shall refer to Jerome Junior here by the name which he adopted when his first book was published – Jerome Klapka Jerome, or JKJ for short.

Though he was born into a genteel, comfortably-off family, JKJ’s childhood proved to be one of hardship and religious fervour. Jerome Senior lost all his money on speculative coalmining when he sank two pits near Cannock in the West Midlands. He moved the family to Stourbridge when JKJ was two, while he went off to take up a failing ironmongery business in Poplar, in London’s East End. Mrs Jerome and her children joined him two years later. The Rev. Jerome proved to be as adept at running an ironmongery business as he had been at speculative mining. So within a few years of JKJ’s birth, the family had descended into abject poverty, poverty which even Mrs. Jerome’s constant prayers to the Almighty did nothing to alleviate. Orphaned at 15, JKJ had few prospects when he began a succession of jobs, first as a clerk with the London and North Western Railway at Euston.

After the railway, Jerome began life as a provincial actor, touring up and down the country, having made his professional debut at the age of eighteen (under the name of Harold Crichton) and, for the next three years, alternately revelled in and despaired of the life whose “glorious uncertainty almost rivals that of the turf”. Three years was enough, but though fame and fortune as an actor eluded him, thereafter Jerome and the theatre never parted company.

My Life and Times was his autobiography published in 1926. In it, he recalled:

“Though I say so myself, I think I would have made a good actor. Could I have lived on laughter and applause I would have gone on. I certainly got plenty of experience. I have played every part in Hamlet except Ophelia. I have doubled the parts of Sairey Gamp and Martin Chuzzlewit on the same evening. I forget how the end came. I remember selling my wardrobe in some town up north, and reaching London with thirty shillings in my pocket… . Fortunately the weather was mild and I was used to ‘sleeping rough’. On wet nights I would have to fork out 9d for a doss house. The best I ever struck was halfway up Pentonville Hill where they gave you two blankets, but one had to be up early for that. Literary gents have always been much given to writing of the underworld. I quite agree there must be humour and pathos and even romance to be found there; but you need to be outside it to discover its attractions. It was a jungle sort of existence.”

So by the time he was in his mid-twenties, Jerome was at the bottom of the social pile, penniless and living in dosshouses. And that might have been that if it hadn’t been for a chance me with a boyhood friend. Jerome remarks in his autobiography that “He too had fallen on hard times and had taken to journalism.”

That was the start of the writing, for though he drifted from journalism, the bug had got him and he spent all his spare time writing short stories, essays and satires and getting rejected. He next tried school-mastering in Clapham, then became in turn secretary to an illiterate north London builder, then a buyer and packer for a firm of commission agents, and lastly worked for a firm of parliamentary agents (today’s professional lobbyists).

Throughout this period he read voraciously and wrote copiously) for he knew, despite his meanderings, that he must be a writer. Only one effort was rewarded with publication, in a paper called The Lamp. ‘It died,’ Jerome recalled, ‘soon afterwards.’ At this time, he had lodgings in a second-floor room at the back of a house in Whitfield Street, off Tottenham Court which enjoyed a view of an extensive burial ground. One evening, he happened to read a collection of poems called by ‘By The Fireside’ by Longfellow, and one of them changed his life. It had the curious title of Gaspar Becerra.

By his evening fire the artist

Pondered o’er his secret shame;

Baffled, weary, and disheartened,

Still he mused, and dreamed of fame.

O thou sculptor, painter, poet!

Take this lesson to thy heart:

That is best which lieth nearest;

Shape from that thy work of art.

Why hadn’t he thought of it before? He would write a book about his life as an actor.

The result was On the Stage – and Off. If you want to know what it was like to be a jobbing actor in the late Victorian age and what a dog’s life it was – this is the book. It’s also very funny, and you can see already the comic timing and the individual turn of phrase that was the making of Three Men. It didn’t achieve instantaneous success. Several periodicals supplied him with the familiar rejection slips. Finally, a new publication came up trumps: The Play edited by a retired actor, Aylmer Gowing.

“He was,” remembered Jerome,” the first editor who up till then had seemed glad to see me when I entered the room. He held out both hands to me and offered me a cigarette. It all seemed like a dream. He told me that what he liked about my story was that it was true. He had been through it all himself, forty years before. He asked me what I wanted for the serial rights. I was only too willing to let him have them for nothing, upon which he shook hands with me again, and gave me a five pound note. It was the first time I had ever possessed a five pound note… I could not bear the idea of spending it. I put it away at the bottom of an old tin box… Later, when my luck began to turn, I fished it out, and with part of it I purchased an old Georgian bureau which has been my desk ever since.”

In 1885 On the Stage – and Off appeared in book form. And that was when he decided to call himself Jerome Klapka Jerome. He was 27 years old.

“The book sold fairly well,” he wrote, “but the critics were shocked. The majority denounced it as rubbish and, three years later, on reviewing my next book, The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow, regretted that an author who had written such an excellent first book should have followed it up with so unworthy a successor”.

Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow, a collection of short essays written with a clever mix of philosophy and humour, became a best seller when it appeared in 1886. People loved its whimsy and informality. In the Preface, we read: “What readers ask nowadays in a book is that it should improve, instruct and elevate. This book wouldn’t elevate a cow.” This was six years before Diary of a Nobody was published, and when P G Wodehouse was five years old. The Victorians had never seen anything remotely like it. But even the book, which appeared three years later, was derided by the critics: “I think that I may claim to have been for the first 20 years of my career,” he says, “the best abused author in England. The Standard spoke of me as a menace to English letters, the Morning Post as an example of the sad results to be expected from the over-education of the lower orders”.

Shortly after Idle Thoughts was finished, Jerome left his graveside panorama and moved round the corner to a front room at 36 Newman Street. In a back room in the same building lived a similarly impecunious young man, a bank clerk named George Wingrave. The landlady suggested that it might be more economical for them to share one room between them and this they did, quickly becoming firm friends. George and Jerome spent much of their spare time and money on visits to the theatre – a common passion, they found – and it was through these visits that they met another theatre-lover, Carl Hentschel. All in all, the theatre was exercising a remarkable influence on Jerome’s life, on the stage and off. And so did the new craze for boating on the River Thames. Every weekend saw crowds of people and flotillas of boats flocking to the river and Jerome, George and Carl were no exceptions.

Jerome’s brief career on stage had also taught him the mechanics of playwriting. By the time Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow had been published, Jerome had already completed his first (one-act) play, Barbara. It ran, on and off, for years. Next he wrote Sunset, an adaptation of Tennyson’s The Two Sisters, and the same year another adaption called Fennel, based on Le Luthier de Crémone by François Coppée. It introduced to the London stage an actor called Allan Aynesworth, who was to become a celebrated player – the original Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest.

At the same time as Fennel appeared, Jerome wrote another book of short essays, another humorous look at the theatre. It was called Stageland. Each section is about the stock characters you could expect to encounter in just about any play of the time – the Comic Man, the Lawyer, the Servant Girl, the Irishman, the Detective, and so on – although in his autobiography, Jerome says that by the late 1920s all these characters had gone from the stage.

Jerome went on to write a further 23 plays, a number of them making a bigger hit across the Atlantic than in England. Among these now forgotten offerings were a couple of farces – Biarritz and The MacHaggis – in which the heroine not only rode a bicycle and smoked a cigarette on stage for the first time, but said ‘Damn’ twice in the last act, years before Mrs Patrick Campbell said ‘Bloody’! His 1902 comedy Miss Hobbs explored what we would call today ‘feminist themes’. The Master of Mrs Chilvers tackled women in politics and equality for women.

But by far Jerome’s most successful play was produced in 1908. It was called The Passing of the Third Floor Back – the story of the

mystical stranger who comes to a run-down boarding house and changes the lives of the rest of the inhabitants. Many saw the stranger as a Christ-like symbol – it is a morality play, devoid of any Jeromian glibness or wit. Though professional revivals these days have been few and far between (there was an excellent one in December 2018 in a London pub theatre), it was performed constantly over the succeeding decades. It ran for seven years in Britain and America, was filmed twice, and starred the greatest Hamlet of his day, Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson as The Stranger.

Though Jerome’s dramatic works have not stood the test of time, I suspect the fact that he was connected to the theatre to such a degree will be news to most people, like the lady who, on one occasion, asked him why he did not write for the theatre: ‘I am sure, Mr Jerome,’ she continued with a bright, encouraging smile, ‘that you could write a play.’ I told her that I had written nine: that six of them had been produced, that three of them had been successful both in England and America, that one of them was still running at the Comedy Theatre and approaching its two hundredth night. Her eyebrows went up in amazement. ‘Dear me, she said, ‘you do surprise me.’

Let us go back a few years. Jerome married in June 1888 – Georgina Elizabeth Henrietta Stanley, known as Ettie. She was a divorcee with a 5 year old daughter called Elsie. Their honeymoon was spent on the Thames. At the same time, Jerome began writing Three Men in a Boat (‘TMIB’) in serial form.

It’s the story of three young bachelors – J, Harris and George – not forgetting the dog, Montmorency – who take a boating holiday on the Thames from Kingston to Oxford. Jerome again was writing from personal experience, for much of the account is based on fact. But that doesn’t account for the book’s success. How did he do it? The late Miles Kington, one of today’s most celebrated writers of humorous prose, gave me the definitive answer. As a young man writing for Punch, Kington bumped into the then editor, Basil Boothroyd, who regaled him with a long, hilarious story about a trip he had taken to Wigan in order to give a speech. It was a journey full of mishaps and ghastly people and terrible weather. Kington was much amused and asked Boothroyd if the story was true?

Never,” said Boothroyd, “never ask a humourist if things really happened.”

“Yes, but did they?” persisted Kington.

“Not in that order, not all on the same day, and not all of it to me.”

George was modelled on George Wingrave who “worked in a bank – well at least, he went to sleep in a bank from ten to four each day, except Saturdays when they woke him up and put him outside at two”. George went on to become manager of Barclays Bank in the Strand, a lifelong bachelor who died in 1941 at the age of 79.

His other close friend Carl Hentschel was re-christened William Samuel Harris. Hentschel / Harris claimed to have been to every London first night since 1879. He was Polish by birth, took over the family printing business and made an important contribution to the development of techniques of newspaper illustration. He died in 1930, aged 65. His obituary in The Times dwelt almost exclusively on his success as a businessman and his distinguished contribution to the City. Only the last sentence mentions that he was Harris in TMIB.

In 20 years, TMIB had sold over 200,000 copies in the UK and over a million in America, though as the States didn’t have any copyright laws at the time, Jerome received nothing in royalties. His publisher JW Arrowsmith said he sold so many copies per annum that he thought the public must eat them. To date it’s been translated into almost every language in the world, including Esperanto, Pitman’s Shorthand, Hebrew, Afrikaans and Sinhalese to name but a few. With this one book, Jerome assured himself of an income for life, found respectability and security, and thirty years of poverty and struggle were over. His friends included H. G. Wells, Kipling, Mark Twain, J. M. Barrie and Bernard Shaw.

Apart from his work as a novelist and dramatist, Jerome co-edited two magazines The Idler and To-Day. Among his contributors were Robert Louis Stevenson, Anthony Hope, W. W. Jacobs, Israel Zangwill, Eden Phillpotts, Arthur Conan Doyle, Bret Harte, Rider Haggard, Arthur Quiller Couch and R. M. Ballantyne. The books continued with Diary of a Pilgrimage, Novel Notes, John Ingerfield, Sketches in Lavender, Blue and Green and, in 1898, The Second Thoughts of an Idle Fellow. He travelled widely, much in demand as a lecturer, and in fact lived in Germany for two years between 1898-1900 with his wife, stepdaughter and their newly-born daughter Rowena,

One of the results of his stay in Germany was a kind of sequel to Three Men in a Boat. In Three Men on the Bummel, J and Harris (both now married)

go off with bachelor George on a bicycle tour of Germany and the Black Forest. One bicycle – one tandem. Parts of this follow-up are just as funny (at times ever more so) as anything in Three Men in a Boat, but the book is also a character study of the Germans, so much so that it was used in that country’s schools as a text book.

For a writer who is now just remembered as a humourist, it comes as a surprise to read that his acute perceptions of the trivialities and frailties of life extended to accurate and weirdly prophetic observations of life in its broader sense. In Three Men on the Bummel, for example, talking about Germany (and remember this was written in 1900):

“Hitherto, the German has had the blessed fortune to be exceptionally well governed; if this continue it will go well with him. When his troubles will begin, will be when by any chance something goes wrong with the governing machine.”

Jerome visited Russia and wrote this in Idle Ideas in 1905:

The workers – slaves it would be almost more correct to call them – allow themselves to be exploited with the uncomplaining patience of intelligent animals. Yet every educated Russian you talk to on the subject knows that revolution is coming. But he talks to you about it with the door shut, for no man in Russia can be sure that his own servants are not police spies… The Russian peasant, when he rises, will prove more terrible, more pitiless than were the men of 1790. He is less intelligent, more brutal. They sing a wild, sad song, these Russian cattle, the while they work… It is a curious song, like the wailing of a tired wind, and one day it will sweep over the land heralding terror.

And what about this, on America from his autobiography:

“The last time I visited America was during the first year of the war [that’s the First World War]. America then was all for keeping out of it. I had friends in big business, and was introduced to others. Their opinion was that America could best serve Humanity in the bulk by reserving herself to act as peace-maker. In the end, she would be the only nation capable of considering the future without passion and without fear. The general feeling was, if anything, pro-German, tempered in the East by traditional sentiment for France. I failed to unearth any enthusiasm for England, in spite of my having been commissioned to discover it. I have sometimes wondered if England and America really do love one another as much as our journalists and politicians say they do.

During a lecture tour of America in 1906, Jerome spoke out against the lynchings of black men and women – and nearly got lynched himself as a consequence. ‘I cannot help thinking,’ he wrote, ‘that if the tens of thousands of decent American men and women, to whom this thing must be their country’s shame, would take their courage in their hands and speak their minds, American might be cleansed from this foul sin’.

Back home he was a vocal supporter of women’s suffrage, and was the guest speaker at the first meeting of the League Against Cruelty to Animals.

Volumes of short stories followed Three Men on the Bummel, further plays and three novels – the autobiographical Paul Kelver, Tommy and Co., and They and I.

‘Of all my books,’ Jerome wrote, ‘I liked writing Paul Kelver the best. I ought, of course, to have gone on. I might have become an established novelist – even a best seller. Who knows? But having ‘got there’, so to speak, my desire was to get away. I went back to the writing of plays. It was the same at the beginning of me. My history repeats itself. Having won success as a humourist I immediately became serious. I have a kink in my brain. I suppose I can’t help it.’

During the First World War Jerome, turned down for active service by the British Army, rejected an offer to join the Home Guard, and another to work in the Clothing Department in Pimlico.

So, quite remarkably, he decided to sign on with the French Ambulance Unit. But he was fifty-six years old and a few months of front-line trench warfare was as much as he could cope with. He was too sickened by what he had seen, and ashamed of his fellow writers for fanning the flames of the Great War. ‘Those who talk about war being a game, ‘he wrote, ‘ought to be made to go out and play it.’

When he returned to England, his secretary observed that the old Jerome had gone. ‘In his place was a stranger. He was a broken man.’ In 1921, his beloved stepdaughter Elsie died suddenly from pleurisy aged 38. Then, in 1927, he and his wife were on a motoring holiday. They had visited Devon, where he suffered a mild heart attack. They returned to London in true Three Men style via Cheltenham and Nottingham to stay at the Angel Hotel. In the middle of the night he suffered a cerebral haemorrhage. He lingered, paralysed, for two weeks and died 14 June 1927.

He is buried in Ewelme, Oxfordshire with his wife Ettie, his step-daughter, and his sister Blandina. Ettie outlived him by 11 years. His daughter Rowena lived until 1966, the last surviving member of the entire Jerome family tree. She never married.

Until a few years ago, the graves were neglected and almost completely illegible. I’m proud to say the Jerome Society funded the restoration of the headstones and are once more in the state that they should be. In May 2009, the day after the 150th anniversary of JKJ’s birth, members of the Society gathered in Ewelme churchyard for the blessing of another Jerome headstone. A few years ago, our late founding chairman, Gordon Foster, was told that a churchyard in Stourbridge had the grave of Jerome’s elder brother, Milton Melancthon. If he wanted to rescue the headstone, he’d better be quick because the churchyard was about to be deconsecrated, tarmacked and turned into an ASDA car park. The Society finally got permission to relocate Milton’s headstone to the churchyard in Ewelme to be reunited with his younger brother. It’s a lovely spot, close to the Thames, and well worth a visit.