Three Men in a Boat & Three Men on the Bummel

The story behind Jerome's two comic masterpieces

by Jeremy Nicholas

President of The Jerome K Jerome Society

Basil Boothroyd, a celebrated editor of Punch, once regaled his fellow-humorist, the young Miles Kington, with the story of a disastrous visit to Wigan where he’d been invited to give an after-dinner speech. One terrible mishap had followed another in the course of the trip and the amused Kington asked Boothroyd if the story was true. “Never,” admonished Boothroyd, “never ask a humorist if things really happened.” “Yes, but did they?” persisted Kington. “Not in that order,” admitted Boothroyd, “not all on the same day – and not all of it to me.”

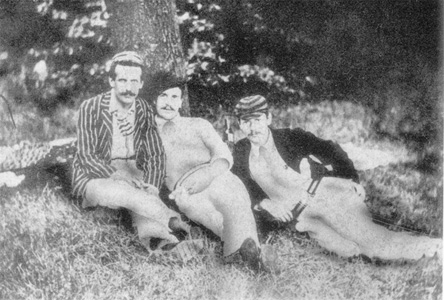

That’s all you need to know about Three Men in a Boat and Three Men on the Bummel. Jerome, as he underlines in the preface to Boat, recorded ‘events that really happened. All that has been done is to colour them; and, for this, no extra charge has been made.’ But surely, you ask, the main protagonists are as fictional as Noddy and Big Ears… aren’t they? Well, no. There really were three friends – George Wingrave, Carl Hentschel and Jerome himself – on whom Jerome based his main characters, who made literally scores of trips up and down the Thames and cycled together across Europe to the Black Forest. However, to then see photographs of these three ‘fictional’ characters actually lounging around on the river bank is the equivalent of hearing Noddy speak: it makes you rub your eyes. Only Montmorency never existed. ‘Montmorency I evolved out of my inner consciousness,’ admitted Jerome. ‘Dog friends that I came to know later have told me it was true to life’.

The original ‘Three Men’ – from left to right Carl Hentschel (Harris),

George Wingrave (George) and Jerome K. Jerome (J).

Jerome was acting as a clerk to a firm of solicitors and lodging just off London’s Tottenham Court Road when Wingrave entered his life. George was a bank clerk (who ‘goes to sleep at a bank from ten to four each day, except Saturdays, when they wake him up and put him outside at two’) and was living in a back room of the same house. The landlady suggested that, to save money, the two might share a room. They ‘chummed’ together for some years – both shared a love of the theatre -and a life-long friendship was formed. George, who remained a bachelor, rose to become manager of Barclays Bank in the Strand and outlived the other two, dying at the age of 79 in March 1941. Carl Hentschel, rechristened William Samuel Harris by Jerome, was born in Lodz, Russian Poland, in March 1864, arriving in England with his parents at the age of five. His father invented the half-tone photographic blocks which revolutionised the illustration of books and magazines and Carl left school at fourteen to join his father’s flourishing business. At only 23 he set up on his own, the start of a long and distinguished career, one which merited an obituary in The Times. (Again, it was the theatre that cemented the friendship with Jerome. Hentschel co-founded The Playgoer’s Club and claimed that, with few exceptions, he had attended every London first night since 1879.) He died in January 1930, leaving a wife and three children. In 1981, during the West End run of his one-man adaptation of Three Men in a Boat, the present writer was introduced to a sprightly, elderly lady. She had much enjoyed the performance, she said, and it was a book she knew extremely well. “You see,” she continued, “Harris was my uncle.”

So there were the ready-made characters, save one little Jeromian twist. Throughout Three Men in a Boat, readers are left in no doubt that Harris is fond of a drink: there is the episode of the swans at Shiplake and the reference to the small number of pubs in the country which Harris has not visited. In fact, Hentschel/Harris was the only teetotaller of the three. There were also ready-made events: for instance, the melodramatic story of the drowned woman at Goring (Chapter 16) is based on the tragic suicide in July 1887 of a Gaiety Girl named Alicia Douglas. Jerome almost certainly read the story in the local newspaper.

A first edition of

Three Men in a Boat

It was only in the mid-1870s that the Thames had been discovered as a pleasure-ground. London was expanding at the rate of knots (to use a suitably nautical term) and the middle- and working-class population suddenly woke up to the recreational potential of the great river, with its towns, villages and watering holes lying only a cheap rail fare away. Boating on the Thames became the latest craze: in 1888, the year in which Jerome wrote Three Men in a Boat, there were 8,000 registered boats on the river; by the following year there were 12,000. Jerome was therefore writing about the ‘in thing’ – the book doubtless swelled the number of boating fans – though the three friends had caught the bug earlier than most. ‘At first,’ recalled Jerome, ‘we would have the river almost to ourselves… and sometimes would fix up a trip of three or four days or a week, doing the thing in style and camping out.’

In other words, plenty of excursions to provide a writer with plenty of material. Jerome had, by this time, been a journalist, his first published book, On the Stage and Off, had successfully used his all-too-real experiences as a professional actor to great comic effect, and The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow had proved his gift as a humorous essayist: a magpie like Jerome would have brought his notebook to the river.

Idle Thoughts had been serialised in the monthly magazine Home Chimes and it was its editor, F.W.Robinson, who took on Jerome’s next project, The Story of the Thames. “I did not intend to write a funny book, at first,” Jerome confessed in his memoirs. The book was to have concentrated on the river’s scenery and history with passages of humorous relief. “Somehow it would not come. It seemed to be all humorous relief. By grim determination I succeeded… in writing a dozen or so slabs of history and working them in, one to each chapter.’ Robinson promptly slung out most of them and insisted that Jerome came up with a better title. “Half way through I hit upon Three Men In A Boat, because nothing else seemed right.”

The first instalment came out in the August issue of 1888, the last in June the following year. Meanwhile. Jerome was wooing the Bristol publishers J.W.Arrowsmith who brought out the book that summer. Had Mr Arrowsmith not accepted, it would have been the literary parallel of Decca turning down the Beatles. Years later Arrowsmith, commenting on the amount of royalties he paid Jerome, confessed he was at a loss to know of what became of all the copies of Three Men In A Boat. “I often think,” he said, “that the public must eat them.”

Years of struggle, deprivation and uncertainty were over for good. Jerome was thirty in 1889, the year which also saw the completion of the Firth of Forth rail bridge, the Eiffel Tower and London’s Savoy Hotel. Three Men in a Boat is now just as much part of the fabric as these noble edifices. Twenty years after it first appeared in hard covers, the book had sold over 200,000 copies in Britain and over a million throughout the United States though, as it was published before the Copyright Convention, Jerome never made a penny from the American sales. Only the German translation outsold the inordinately-successful Russian edition. To date it has been published in almost every language in the world including Japanese, Pitman’s Shorthand, Hebrew, Afrikaans (Drie Swape op De Rivier), Irish (Triur Fear I Mbad) and Portuguese (Tres Inglises No Estrangeiro). It has been adapted into every performance medium – filmed three times (1920, 1933 and 1956), televised by Tom Stoppard, turned into a musical by Hubert Gregg, made into a stage play on several occasions, read aloud on radio and spoken-word cassette numerous times and, at least twice, done the rounds as a one-man show. Three Men in a Boat, incidentally, enjoyed the rare distinction of coming out of copyright (in 1977, fifty years after the author’s death), then going back into copyright (for just one year, 1996) after new laws extended copyright to seventy years. It has never been out of print.

A rare photograph of the original ‘Three Men’ L to R:

Olga Hentschel, Jerome, Carl Hentschel (‘Harris’),

unknown lady, George Wingrove, Effie Jerome (JKJ’s wife)

In a foreword to the 1909 edition Jerome remained puzzled as to the reasons for the undiminished popularity of Three Men in a Boat. He had, he believed, ‘written books that appeared to him more humorous’. But then Beethoven could never understand the popularity of his ‘Moonlight’ sonata, complaining that he had written far better works. Not that Jerome ever occupied the same Olympian heights as Beethoven; no one has ever mistaken him as a great literary thinker. (Somebody once accused H.G.Wells of ‘hiding his intellect and trying to pass himself off as another Jerome’.) He was not a virtuosic comic novelist able to concoct the joyously-improbable plots of a Wodehouse, Waugh or Tom Sharpe (though it is extraordinary how many people assume that Jerome was a contemporary of Wodehouse). Extended forms were not Jerome’s forte. He was better at the scherzo than the symphony. Within these limitations he was a master. He knew all about comic timing, how to transfer it intact to the page ‘live’ – and how to polish. Compare the opening paragraph of Three Men in a Boat with the clumsy opening passage as it first appeared in Home Chimes:

“There was George and Bill Harris and me – I should say I – and Montmorency. It ought to be ‘were’: there were George and Bill Harris and me – I, and Montmorency. It is very odd, but good grammar always sounds so stiff and strange to me. I suppose it is having been brought up in our family that is the cause of this. Well, there we were, sitting in my room, smoking, and talking, and talking about how bad we were – bad from a medical point of view, I mean, of course.”

Nevertheless, there are long passages of mawkish purple prose (the end of Chapter Ten, for example, with the ‘goodly knights’ riding through the deep wood) that must have made readers wince even in 1889. It is as though Jerome felt obliged to insert a four-part fugue in the middle of a popular song, merely in order to give the critics something to chew. The construction of the book, too, is lop-sided: we are nearly a third of the way through the book before anyone rows a stroke, and the return journey is accomplished in eleven brief pages (out of 315). Its shortcomings have never mattered one jot to succeeding generations of devoted fans.

What was entirely new about Boat was the style in which it was written. Conan Doyle, Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling and Robert Louis Stevenson were widely read and highly popular but Jerome differed in two respects: his story was not of some fantastical adventure in a far-off land, peopled by larger-than-life heroes and villains, but of three very ordinary blokes having a high old time just down the road, so to speak; and, in an age when literary grandiloquence and solemnity were not in short supply, Jerome provided a breath of fresh air. In the preface to Idle Thoughts, Jerome had set out his stall: ‘What readers ask now-a-days in a book is that it should improve, instruct and elevate. This book wouldn’t elevate a cow.’ He used everyday figures of speech for the first time (‘colloquial clerk’s English of the year 1889’ as one critic described it) and was very, very funny. The Victorians had simply never come across anything like it.

Jerome photographed in Monks Corner, his house in Maidenhead,

beneath the portrait of him by De Laszlo

Jerome was taken to task by the serious critics. They hated the ‘new humour’, the ‘vulgarity’ of the language and its appeal to the ‘Arrys and ‘Arriets (a term coined by the middle-classes to describe the lower-classes and those who dropped their aitches). Punch dubbed Jerome ” ‘Arry K. ‘Arry”. ‘One might have imagined,’ JKJ recalled, ‘that the British Empire was in danger… The Standard spoke of me as a menace to English letters; and The Morning Post as an example of the sad results to be expected from the over-education of the lower orders… I think I may claim to have been, for the first twenty years of my career, the best abused author in England.’ Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Boat is that, compared with almost all its contemporaries and despite Jerome’s wide use of then- fashionable colloquialisms, the book has dated very little.

Three Men On The Bummel (Three Men on Wheels as it appeared in America) is often unfairly chastised as being an ineffectual afterthought. True, it is not on the same exalted level, but it is written with the same verve and energy, and the set pieces (the boot shop, Harris and his wife on the tandem, Harris confronting the hose-pipe, the animal riot in the hill-top restaurant) are as polished and funny (funnier, some would say) as anything in the earlier book. Much time is spent, to the reader’s smug self-satisfaction, observing the peculiarities of the German nation and its people with wry amusement and not a little affection (the schools of Imperial Germany, with characteristic earnestness, adopted it as a textbook). Jerome is also uncannily perceptive about the political catastrophes that were so shortly to overtake the country. But too often one loses sight of the bummel itself, the book’s raison d’être.

The trump card that Bummel lacks, and which makes Three Men in a Boat what it is, is the River Thames. It provides the framework for Jerome’s discursive narrative. He can stray from the present adventure as much as he likes, he can stop for his set pieces whether they be on the river or elsewhere, he can recall events from previous trips (the cheeses taken from Liverpool to London, the visit to Hampton Court maze), but the river holds the whole thing together and gives the book its satisfying unity. The best television situation comedies rely on this same device, a world with clearly-defined parameters. A ramble through Germany and the Black Forest does not provide that.

None of this fully explains the popularity of Jerome’s masterpiece. Perhaps it’s a pointless exercise, like pulling off the wings of a Red Admiral to see how it flies. Jerome concluded that ‘be the explanation what it may, I can take credit to myself for having written this book. That is, if I did write it. For really I hardly remember doing so. I remember only feeling very young and absurdly pleased with myself for reasons that concern only myself.’

Miles Kington tells a story that encapsulates perfectly the art of the English humorist as personified by Jerome and exemplified in these two life-enhancing books. Basil Boothroyd had just returned from holiday. Kington bumped into him. “Hallo, Basil. Have a good holiday?” “Awful,” replied Boothroyd. “Nothing went wrong at all.”

©Jeremy Nicholas 2007